Hasyim Mohamad al-Baghdadi (1917-1973)

Hāshim served as a calligrapher in the Surveyors' Department in Baghdad from 1380/1960 until he was transferred to the Ministry of Education, where he was appointed head of the Department of Decoration and Calligraphy in the Institute of Fine Arts.

Hāshim was deeply influenced by the Turkish calligraphers. He greatly admired the work of Hāfız Osman; Mehmed Şevki; Hacı Ahmed Kāmil Akdik; and Hāmid Aytaç. His admiration for Mustafa Rākım was so great that he named his son after him and began calling himself Abū Rāqım, or Rāqım's father. In İstanbul, he used to visit Necmeddin Okyay, who owned a distinguished collection of calligraphic works.

In addition to kıt'as, hilyes, and levhas, Hāshim calligraphed decorative friezes in mosques and other buildings in Baghdad and other cities; these were done on faience or marble, mostly in jalī thuluth. The rarest of his works are in kūfī script, as in the ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī Mosque and the Hājj Mahmūd Mosque. Hāshim al-Baghdādī died on 27 Rabī‘I 1393/30 April 1973 in Baghdad and was buried in the Khayzuran Cemetery.

Source: Waleed al-'A'zamī, Tarajimu khattati Baghdad el-Muasirin, Beirut 1977, p.254-75. http://ircica.org

Osman ÖZÇAY

In 1982, even though he did not have a special interest in Islamic calligraphy, he joined his brother when he first visited calligrapher Fuat Başar. He was suddenly attracted to the art and he started lessons in the script Thuluth the same day. He later received his diploma in the scripts of thuluth and naskh from his teacher.

When he came to Istanbul, he met M.Uğur Derman from whom he has benefited greatly throughout the years. Mr. Derman gave him some copies of Sami Efendi`s Jali Thuluth writings which were written for a public water fountain behind `Yeni Cami` (New Mosque) in Istanbul. These sources served as the most important guide in learning the script of Jali Thuluth.

In the first (1986) and second (1989) international competitions organized by The Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA) which serves as the secretaryship of The Commission for the Preservation of Islamic Cultural Heritage associated with the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, he received five awards, gaining second and third prizes in various scripts including Jali Thuluth and Thuluth. He won the first prize at the calligraphy competition organized by the Maktab al-Shahid Kuwaiti institute in 1997.

Osman Özçay has participated in personal exhibitions with his brother Mehmet Özçay in Istanbul (1996), Abu Dhabi (1998), Sharjah (1999), and Dubai (2003). He has also taken part in the exhibitions organized by IRCICA in association with the Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing in Dubai 2003, 2004 and 2005. In 2003, he participated in the calligraphy exhibition in Tokyo and joined some other calligraphers on The Days of Arabic Calligraphy in Tunisia in 1997 and 2006. He has also participated in various exhibitions in Turkey and abroad.

Osman Özçay is producing works in the styles of thuluth, jali thuluth, naskh and muhaqqaq according to the classical approach. Throughout the years his pieces of calligraphy have entered museums and special collections.

source: www.ozcay.com

Mehmed ÖZÇAY

Mehmed Özçay was born in 1961 in the Çaykara district of the province of Trabzon, in Turkey. He completed his elementary and secondary education in Gerede, subsequently graduating from the School of Theology of Atatürk University, Erzurum, in 1986. He studied naskh and thulth scripts with the calligrapher Fuat Başar, whom he met there in 1982. In 1986, he moved to İstanbul where he met M. Uğur Derman, who became his guide in calligraphy; this gave him the opportunity to broaden his horizons and deepen his appreciation for, and knowledge of, this art.

Mehmed Özçay was born in 1961 in the Çaykara district of the province of Trabzon, in Turkey. He completed his elementary and secondary education in Gerede, subsequently graduating from the School of Theology of Atatürk University, Erzurum, in 1986. He studied naskh and thulth scripts with the calligrapher Fuat Başar, whom he met there in 1982. In 1986, he moved to İstanbul where he met M. Uğur Derman, who became his guide in calligraphy; this gave him the opportunity to broaden his horizons and deepen his appreciation for, and knowledge of, this art.In 1986 and 1989, Özçay participated in the first two international calligraphy competitions organized by the Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture (IRCICA), winning six prizes in various categories, most notably First Prize in thulth-naskh scripts. He began to copy the Holy Qur’an in 1986; completed in 1991 and first published in 1992, that work has played a key role in the development of his mastery of naskh script, and more generally in the establishment of his career as a professional calligrapher. Fine art reproductions of his copy of the Surat Ya-Sin, as well many of his panels, have also been published...

Özçay participated in many exhibitions, both in Turkey and internationally—including the Kazema Festival for Islamic Heritage (Kuwait, 1996), the Islamic World Calligraphy Festival (Tehran, 1997), Seven Ottoman Arts that have Lived Beyond 700 Years (İstanbul, 1999), the Riyadh Calligraphy Exhibition (1999), the Holy Qur’an Exhibition (Tehran, 2000), the National Calligraphy Festival (Tunis, 2001), the Tokyo Calligraphy Exhibition (2003), Salam & Calligraphy (Doha, 2003), the Sharjah International Biennal for Arabic Calligraphy (2004), the Dubai International Calligraphy Exhibitions (2004, 2005, 2006), and the Tunis Arabic Calligraphy Days (1999, 2006).

Mehmed Özçay’s first individual show was held in conjunction with his brother Osman Özçay and his sister Fatma Özçay in May 1996 at the Yıldız Palace, İstanbul. He subsequently partook in the “Özçay” exhibitions at the National Culture Foundation (İstanbul, 1998), in Doha (November 1998), Abu Dhabi (December 1998), Sharjah (1999), and Dubai (2003). He has also served as a member of the jury in a number of international calligraphy competitions.

More than 300 of Mehmed Özçay’s calligraphic panels in jali thulth, thulth, naskh, ijazah, and jali diwani scripts are currently in various collections both in Turkey and abroad.

source= http://www.ozcay.com

AKLAM, Calligrapher Association in memoriam

As far as I know, AKLAM is the abbreviation of Associations Kaligrafer Darussalam. A Group of Calligraphy Lover in Modern Building School Gontor. Where, I also had learn calligraphy there, and become members.

Given the means AKLAM remember when we first learn handwriting in the Saudi Building Level III VI. And sometimes must take extra training in night after night absent, to the senior asatidz. Moreover, if Friday night came, rushing we had even centered in the 'markaz', the secretariat studio. Office of the narrow building in Tunis is the usual throng of children who are making mading ....

Yes, from the first AKLAM gave me many things about calligraphy, although it is still raw and basic, but that is the case that gives me spirit to survive to keep my art is taken.

And, thank you, and create a nostalgic AKLAMAN 2001. Wempi, Sofi, Seta, Surya, Angga, Kusna, Hekky, Ruslan and all alone ... I miss U all bro ... when we expedisi again ... Want to go ahead TURKEY guys?!

The Calligraphy of Anna Zhao

I recently had a lovely visit from Richmond’s Anna Zhao, who studies and practices calligraphy in the Shou Jin style. She came bearing gifts — including this gorgeous fan on which she had written my name.

She gave me this background information: The ‘Shou Jin’ style (literal translation being “slender gold”) was developed by empire Zhao Jie of the Song dynasty from AD1082-1135.

He was a very talented artists gifted in various forms of artwork including water colour painting and stamps. He was also known to have hosted many events promoting and celebrating various forms of art. The ‘Shou Jin’ style was carried on to his son Zhao Gou who further developed the structure and appearance.

Zhao Jie and his son Zhao Gou are regarded as an odd pair in Chinese history because it was rare for a father and his son to become calligraphers when being a part of a Chinese royal family. Although they are well respected and admired by millions of Chinese today for their art, they were both bad with dealing with country affairs. That is the reason for the idiomatic saying “Doing things as badly as the empire of the Song dynasty” we often hear today.

Thank you, Anna!

Unsung Heros, Unsung Scribes

Strangely, it didn’t occur to me that when the Calligraphy Society of Ottawa invited me to teach a two-day workshop, that I’d be meeting Canada’s “national scribes”. Perhaps that was for the best. Had I understood that earlier, I would have been very intimidated by those in attendence at my evening slide presentation and weekend workshop!

Though I had been to Ottawa many times, I confess I had never visited our national Memorial Chamber located in the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill, and was unaware of The Books of Remembrance displayed there.

I had a day to spend in Ottawa, and my excellent hostess, Pat Gregoire, whisked me off to ‘The Hill’ to see the books, chatting to me about the scribes who wrote them and sharing anecdotes about their work. It was a beautiful November day, just several days prior to Remembrance Day, and the green lawns of Parliament Hill were full of visitors. But in the vaulted Memorial Chamber, we grew quiet while examining the books — marvelling at the craftsmanship, but also keenly aware of the larger significance of these massive volumes — each and every name represents one life lost in service to our country.

As a scribe, I can well imagine the enormity of taking on such a task. First of all, nerves of steel are required. Though these pages are intentionally simple when compared to some manuscripts (we’re SO Canadian!), each page still involves painstaking hours of work — including watercolour illustrations, heraldic paintings and illumination.

Pat examined the pages closely, picking out the penmanship of various scribes. We don’t know all the names of the scribes involved, but we do know that John Whitehead, the founder of the Calligraphy Society of Ottawa, was both a scribe and mentor to the calligraphers who work on the books today.

I will be writing more about these books — their depth and historic importance deserve more than one blog post. But I will sign off this post urging anyone visiting Ottawa to take some time for The Peace Tower. If you’re Canadian, like me, your impression of Parliament Hill may be largely set by bickering politicians on the evening news.

Who knew the pride and pleasure of being Canadian could be rekindled by an impromptu visit to ‘The Hill’?!

___

Shown above, top to bottom:

The Second World War Book of Remembrance honours over 44,800 Canadians who died in the 1939-1945 war.

The South Africa - Nile Expedition Book of Remembrance contains the names of 283 soldiers killed between 1899 and 1902, and 1884-85 respectively.

The Newfoundland Book of Remembrance honours the 2,363 Newfoundlanders who died during World War 1 and World War 2.

The In the Service of Canada Book of Remembrance, the most recent book added in the Memorial Chamber honours those who continued a Canadian tradition of selflessness and courage and offered the supreme sacrifice in the military service of our country since October 1947.

Sue Fraser: A Tribute

Calligraphers, at least most of them that I know, are a pretty laid back bunch. So when I started attending the events of the Fairbank Calligraphy Society, Sue Fraser quickly stood out. She was the one making wisecracks in the serious meetings, sat at the rowdiest table at our yearly YellowPoint gathering, and just generally lightened the mood of any room she entered. She also stood out as a talented watercolourist and calligrapher.

A trip to Tuscany in 2006 resulted in a spectacular watercolour journal of over 30 pages. (Two pages are shown above.)

Sadly, my friendship with Sue was relatively short... we lost her to cancer this summer... but even while ill, she was planning a party. So, last weekend, along with her family, friends and members of both the West Coast Calligraphy Society and Fairbank Society, I attended the Celebration of Life for Susan Logie Fraser.

Sue’s calligraphy on the invitation included these words, “I’d like the memory of me to be a happy one... I’d like to leave an after-glow of smiles when life is done, I’d like to leave an echo whispering soft down the way... ”

What a bittersweet event – there were tears and laughter as we remembered Sue. Her plans for the day included members of the Fairbank Society creating weathergrams (tags on which were written memories of Sue) which we hung on a potted tree and gave to her husband, Chris. There was excellent music, (including an original tribute composed by her son-in-law) wine and food, and lots of Sue’s wonderful art. Sue’s young grandchildren handed out cards featuring her calligraphy, to each guest. I received the one shown below, “Do not stand by my grave and weep...”

As I put the final touches on plans to teach in Ottawa in November – teaching a workshop that Sue first suggested I teach and helped me to organize, I have to pause and think of Sue. And smile. In her after-glow.

Ibrahim Abu-Touq

More beautiful Islamic art, this time the work of Jordanian calligrapher, Ibrahim Abu-Touq. This piece is called "Disappeared 1".

Arabic Calligraphy Exhibition at Saqiyah el-Shawiy

Ramadhan karim…kullu sanah wentum bikhair. Hari kelima bulan Ramadhan yang lalu saya pergi ke Zamalek. Tepatnya ke bawah kubri (jalan layang) di ujung kota tersebut. Markas Budaya “Saqiyah abdul Mun’im ash-Shawiy”. Beruntung sekali ada kawan Mesir yang memberi tahu bahwa hari ini adalah pembukaan pameran khot oleh “Jam’iyyah Mashriyyah Ammah lil Khattil Arabiy”. Selain itu ada pameran tunggal oleh khottoth Hasan Hasubah asal Port Sa’id, yang digelar hingga 10 Ramadhan.

Pameran kaligrafi tersebut dibuka untuk umum mulai kemarin Jum’at (5/09) hingga akhir bulan Ramadhan, mulai pukul 09.00 pagi hingga pukul 15.00 siang. Kemudian buka untuk kedua kalinya setelah tarawih, atau sekitar pukul 21.30 malam hingga menjelang sahur.

Tidak banyak sebenarnya karya yang dipajang, hanya saja beragam. Ada 10 orang kaligrafer yang berpartisipasi melalui karyanya dalam pameran ini. Dari kaligrafer senior seperti khattath Muhammad Hammam, Khattath Musthafa ‘Imari, Fannan Musthafa Hudair, Mahmud Bargawi, hingga sederet nama kaligrafer muda seperti Romi dan juga kaligrafer putri mesir, Manal. Meskipun beberapa karya yang ada adalah karya-karya ‘tua’ yang juga sering nongol di pameran-pameran kaligrafi sebelumnya, namun pameran kaligrafi kali ini tetap saja sayang untuk dilewatkan…

Beberapa gambar pameran dan fannan (seniman) yang hadir dalam pembukaan pameran.

Noble Calligraphers

The lines of calligraphers have neither beginning nor end as they constantly link and unlink. The calligrapher's work lies in search of the absolute; his aim is to penetrate the sense of truth in an infinite movement so as to go beyond the existing world and thus achieve union with God.

-- Salah al-Ali (quotes in Musee d'art et d'histoire. "Islamic Calligraphy: Sacred and Secular Writings". Catalog of an exhibition held at the Musee d'art et d'histoire, Geneva and other locations 1988-1989, p. 30)

Calligraphers were dedicated to their work. David James writes in Sacred and Secular Writings (1988, p.22) that calligraphers often wrote, not at a small table but seated on the floor, holding the paper on their knees and supporting it with a piece of cardboard. Calligraphers had to be trained from a young age, sometimes from childhood; they studied examples called mufradat which had the letters of the alphabet written out singly and in combination with other letters.

The great calligraphers could write perfectly even without the proper tools and materials. Although a calligraphic master might be deprived of the use of his preferred hand either as a punishment or in the battle field, he would learn to write equally well with his other hand. When the other hand failed him, he would astound his admirers by using his mouth or feet to hold the pen.

An aspiring scribe would observe his predecessors' art very carefully. To perfect his touch, sharpen his skills, and find a style of his preference, the scribe would imitate the masters of calligraphy with a diligent hand. Welch (1979, p. 34) cites the following quote from the Sultan Ali's treatise on calligraphy:

Collect the writing of the masters,

Throw a glance at this and at that,

For whomsoever you feel a natural attraction,

Besides his writing, you must not look at others,

So that your eye should become saturated with his writing,

And because of his writing each of your letters should

become like a pearl.

Ibn al-Bawwab reproduced the writing of Ibn Muqlah so exactly that his employer, the Buyid amir Baha' ad-Dawlah of Shiraz, could not tell the difference.

Arabic calligraphers integrate inner experiences with their experiences of external reality. By imbuing strokes with life and feeling, an equilibrium of energy flows from all composing elements. A calligrapher's integration of inner and external realities results in a very personalized style and is accompanied by concentrated and unremitting scholarly study. The development of a calligraphy style is as unique as the calligrapher's personality, and its achievement is considered as the representation of the individual's self-cultivation.

It is fascinating to think how great calligraphers such as Ibn Muqlah, Ibn al-Bawwab, and Yaqut al-Musta'simi strove for knowledge and made use of all possible resources from the past.

In almost all of the Arabic scripts, the spacing between lines and words overflows with a sense of freedom and a flexibility that reveals the creativity and spontaneity of the calligrapher. Through the calligrapher's momentum and sense of balance, a tranquil harmony is achieved that immediately appeals to the mind and to the heart. (http://www.islamicart.com)

Islamic Calligraphy

Arabic is written from right to left, like other Semitic scripts, and consists of 17 characters, which, with the addition of dots placed above or below certain of them, provide the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet. Short vowels are not included in the alphabet, being indicated by signs placed above or below the consonant or long vowel that they follow. Certain characters may be joined to their neighbors, others to the preceding one only, and others to the succeeding one only. The written letters undergo a slight external change according to their position within a word. When they stand alone or occur at the end of a word, they ordinarily terminate in a bold stroke; when they appear in the middle of a word, they are ordinarily joined to the letter following by a small, upward curved stroke. With the exception of six letters, which can be joined only to the preceding ones, the initial and medial letters are much abbreviated, while the final form consists of the initial form with a triumphant flourish. The essential part of the characters, however, remains unchanged.

These features, as well as the fact that there are no capital forms of letters, give the Arabic script its particular character. A line of Arabic suggests an urgent progress of the characters from right to left. The nice balance between the vertical shafts above and the open curves below the middle register induces a sense of harmony. The peculiarity that certain letters cannot be joined to their neighbors provides articulation. For writing, the Arabic calligrapher employs a reed pen (qalam) with the working point cut on an angle. This feature produces a thick downstroke and a thin upstroke with an infinity of gradation in between. The line traced by a skilled calligrapher is a true marvel of fluidity and sensitive inflection, communicating the very action of the master's hand.

Arabic calligraphy, thus, is the art of beautiful or elegant handwriting as exhibited by the correct formation of characters, the ordering of the various parts, and harmony of proportions.

In the Islamic world, calligraphy has traditionally been held in high regard. The high esteem accorded to the copying of the Quran, and the aesthetic energy that was devoted to it, raised Arabic calligraphy to the status of an art. Arabic calligraphy, unlike that of most cultures, influenced the style of monumental inscription. It is revered as highly as painting. (Courtesy: Arabiccalligraphy.com)The Arabic alphabet

The full alphabet of 28 letters is created by placing various combinations of dots above or below some of these shapes. (An animated version of the alphabet shows the correct way to move the pen).

The three long vowels are included in written words but the three short vowels are normally omitted – though they can be indicated by marks above and below other letters.

Although the Arabic alphabet as we know it today appears highly distinctive, it is actually related to the Latin, Greek, Phoenician, Aramaic, Nabatian alphabets. Other languages – such as Persian, Urdu and Malay – use adaptations of the Arabic script.

The numerals used in most parts of the world – 1, 2, 3, etc – were originally Arabic, though many Arab countries use Hindi numerals.

Cleaning your Pilot Parallel Pen

Also, Anonymous, take your Pilot Parallel pen apart as far as possible... that means right down to pulling out the two metal plates which form the nib. Soak the parts, then rinse and reassemble. Should work.

Another reader also suggested using a ultrasonic cleaner, which I haven't yet tried, but which sounds great.

More Malik

For those visitors who listened to our CBC radio interview, here’s a direct link to the pages of Malik Anas, who continues to produce amazing contemporary Iraqi calligraphy.

Monograms

I’ve been creating monograms lately ... using the 6.0mm Pilot Parallel pen and my favorite colour of J.Herbin ink, “Ambre de Birmanie”. Some letters are just so much fun! Like N and K.

On Air!

Summer’s over... back to work

Okay, so I’ve been neglecting this blog! Blame it on the sunshine, the lure of a Canadian summer... maybe too much time spent on facebook or youtube...

Anyway, summer is pretty much over, so I’ll start sharing some of the new links and work I’ve discovered. Let's start with the interesting work of Nikheel Aphale (not Nikhil!) of New Delhi, India. His blog felt so familiar to me... and I love his pieces which combine photography and calligraphy, like this.

Letters in the blood?

Which leaves me wondering: this strange interest in letters I have — which seems quite out of place compared to the interests of other members of my family(!) — does it possibly run in the blood? I wonder if any other calligraphers out there have discovered a link to an earlier scribe? Would love to hear from you if you have.

Calligraphy on CBC Radio...

My first gilding!

I just sent an email to Georgia Angelopoulos, writing ‘I WANT MORE GOLD!’ I’m not usually so demanding(!), but I just completed the homework for Georgia’s class, and my first semi-successful attempt at gilding. I’m hooked. Georgia had been asking if we wanted her to order some gold leaf for us... and, until I finished this piece, I wasn’t that keen on it... but now, I DO want more! More, so I can continue to learn how to use it — it’s fickle material — and more so I can re-do this piece properly. For now, it stands, full of ‘lessons learned’ as my first piece of gilding... and though I clearly have a lot to learn about gilding, the overall ‘feel’ of the piece is really enhanced by the gold.

Thanks, Georgia, for bringing out the traditionalist in me! (I wasn’t sure there was one!) Next, of course, there will be the challenge of learning how to photograph gilded work...

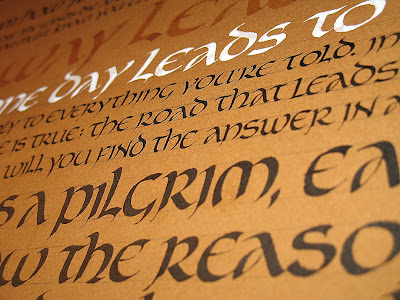

Uncials and Beyond...

The Fairbank Calligraphy Society is conducting an 8-week course led by Georgia Angelopoulos, with Lorraine Douglas, Kathy Guthrie and myself contributing. The focus is on uncials, and it’s been fun to revisit these letterforms with Georgia as a guide. Above is my homework assignment... text is Enya’s lyrics, “Pilgrim”. I wish I had taken my camera to class, because all the work of the students laid out together was very impressive!

I recorded myself by my cell phone ... I will make sure I put new and better ones in the near future.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfyq9dlim7s

30 January 2008